LBP is the most prevalent musculoskeletal disorder and leading cause of disability - 84% of the population will experience LBP over their lifetime, of which 90% will present as non-specific lower back pain which cannot be attributed to a known cause or identified spinal pathology2. LBP can really affect people’s lives, in 2018 70% of Australians with LBP reported that it interfered with their daily activities to at least some extent and around 15% experienced high psychological distress

Ultimately, the role of any intervention is to reduce pain and increase function, especially in the early stages to ensure adherence to the rehabilitation program. The prognosis for acute LBP is generally positive with approximately 72% recovering within 12 months, however the rate of recurrence over the next year following recovery are common, in fact 24-87% of individuals who recover from LBP with have a recurrence within the next year3.

We know that exercise is good for LBP, it is considered fundamental in the management of LBP and is advocated as the first line of treatment. Over 90% of clinical guidelines from Australia and around the world recommend exercise therapy and all recommend a multi-disciplinary approach to treatment (GP, specialists, exercise physiologists, physiotherapists, etc)4. Exercise is one of the few clearly effective interventions with strong evidence to support the use of structured programs for both treatment & prevention. Over 95% of surveyed physiotherapists and exercise physiologists prescribe advice to stay active and exercise for sufferers of LBP. Several exercises were regularly cited and included aerobic (up to 85% of clinicians), motor control (up to 84%), range of motion (75%) and strengthening exercises (> 60%)5. These recommendations have a strong evidence-base, with the literature on the topic generally looking at core stability, lower back strengthening, and general exercise to improve motor control, strength, endurance, flexibility, range of motion, and general fitness. But the evidence is inconsistent regarding just what sort of exercises are most effective in treating LBP. There is no hard and fast evidence that any one type of exercise is greater than another.

Exercise interventions are going to be most effective when they are targeted to the specific neuromuscular impairments experienced in each case. Exercise programs based on identified patient-specific tailored interventions can drastically improve outcomes2.

Motor Control Exercises

Motor control exercise (MCE) is a common form of exercise used for managing LBP and focuses on the activation of the deep trunk muscles to restore their control and coordination, progressing to more complex and functioning tasks6. For chronic LBP, more so than acute, there is some evidence that MCE is effective for reducing pain, and a meta-analysis determined that MCE had favourable outcomes for improved short-, medium- and long- term pain & disability7.

Individuals who performed an 8-week program of high load lifting exercise with low load motor control exercises reported decreased pain and disability at 2, 12, and 24-month follow ups8. Motor control exercises were used to teach individuals to activate stabilising muscles to control the lumbar spine in neutral positions in while seated, supine, four-point kneeling, and standing, with movements of the arm and legs progressively introduced.

Core Stability & Strengthening

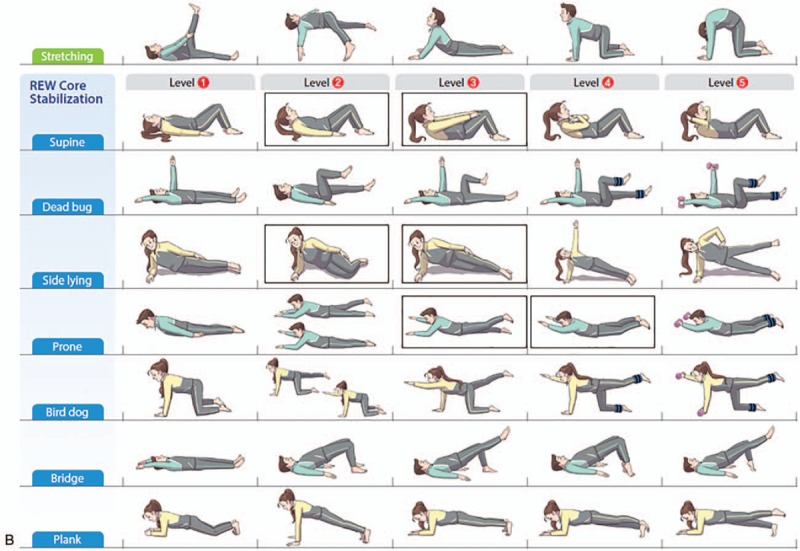

Core stability is essential for proper load balance within the pelvis and spine, so core stability exercises are a commonly used exercise treatment regimen. Core stability and strengthening exercises are used to achieve spinal stabilisation by strengthening the inner unit muscles responsible for stabilising the trunk, pelvis, and lower back and are considered the primary treatment for LBP. Stabilisation exercises improve pain and disability compared with general exercises and should be considered in conjunction with manual therapy9. Core exercises appear to be most effective during the initial 3 months of the intervention, and major improvements in pain and disability have been demonstrated10. Stabilisation programs can be individualised using various postures of progressive intensities to meet the specific needs of the individual11. Examples of core strengthening exercises, and their progressions, are shown in the diagram.

Walking

The best exercise though? Walking! It produces low levels of passive tissue loading and prolonged activation of supporting musculature, although it is essential that this is performed with correct posture. Walking is cost effective and has high levels of adherence and has been shown to be just as effective as other forms of exercise and physiotherapy interventions on functional disability, pain, & quality of life12. In 2019, Suh11 showed that a walking program to rehabilitate LBP patients of 30mins 5 time a week for 6 weeks had favourable effects on muscle strength and endurance and effectively reduced pain and improved function. Walking is also highly recommended to rehabilitate patients with LBP as it leads to enhanced isometric endurance.